In her quintessentially-Gen-Z novel Yellowface, Author Rebecca F. Kuang weaves the casual cadence of internet slang with the poise of a real satirical work. Yellowface is a berserk commentary on envy, racial biases and the struggles of being a young author. This first-person narrative is told by Juniper (June) Hayward. A Yale graduate from Philly with a sore publishing debut, struggling to establish herself within the industry. She fosters a corrosive envy of Athena Liu, a renowned Chinese-American author and an old classmate. Although circumstantial and impersonal, their friendship continues after college and into their professional careers where they both end up in Washington D.C.

Kuang allows the reader to shamelessly indulge in the hate directed towards the archetype of the It-Girl which Athena embodies. It’s in the hilarious way June takes offense at everything Athena does, despite Athena doing no real harm. Infuriatingly flawless; congenial, pretty, skinny and successful. Athena “outshines you at every turn.” Kuang writes. June believes that becoming a best selling author entails more than just producing a great body of work. The industry simply picks a “winner” to pour all the resources into. This person has to check certain boxes such as being attractive, young and most importantly “diverse”. Athena taunts June with her aloofness, tone-deafness and glamour. And June knows that Athena only clings to her because she understands her world without imposing the threat of competition.

One evening, as the duo is hanging out in Athena’s fancy apartment, Athena chokes on food and dies. What seems an understandable jealousy turns out to be a destructive resentment when June steals a manuscript from Athena’s office before existing the site. She goes on to rewrite and publish it as her own, claiming that she has been inspired by -now her closest friend and muse- Athena. Titled The Last Front, the book is about the Chinese Labor Corps in World War I. And for the first time in her life, June experiences what it’s like to be a celebrated bestselling author, what it’s like to be like Athena.

As she plagiarizes another work of Athena’s, making another successful book, June starts to experience what seems like psychoses or worse; seeing a ghost. She starts seeing Athena herself in public places. In the meanwhile, Candice Lee from June’s agency team starts to suspect her. The nature of that book in addition to June’s attitude towards editing it and her utter refusal to hire a sensitivity reader, all allude to one thing. The book is stolen from the deceased bestie. As the inevitable accusations and rumors spread, June teeters on the edge of madness. She finds herself tormented by the immutable guilt, the ghost of Athena, and the fear of being exposed and losing her career.

By brining the minority group factor into the conversation, Kuang allows herself to highlight the racial prejudice in the industry. Starting with the asianfication of June, whose full name is Juniper Song Hayward with Song being her middle name, chosen by her formerly hippie mother. The agency rebrands June Hayward as Juniper Song, exploiting the Asian sounding middle name to give her that flair of racial ambiguity that sells. June never claims to be of Asian descent, however, the name Song on a book about Chinese history is likely to convey a very particular impression in America.

In the final confrontation in the novel, Athena’s truth is lost between June and Candice Lee. June laments over the patronization of ordinary white women and being reduced to only that. She thinks Athena capitalized on being Chinese, taking advantage of the industry’s hunger for diversity and that her success can only be credited to being diverse and beautiful. In comparison, she herself is “just brown-eyed brown-haired June.” She even recalls how Athena hated her fellow diverse writers and rendered their accounts of racial discrimination as redundant and overused — respectfully insane take by Kuang. In return, Candice Lee explodes, telling all about the industry’s exploitation of ethnic writers. Because that’s the type of stories people want to hear, Athena was confined within “the exotic Asian girl trope.” she says. The dead author was only ever allowed to write about her father’s suicide and her nation’s tragedy. Finally, Candice also speaks of her own misery as an Asian woman in the industry. She confesses she felt as though there was no place left for her in the D.C. scene, since the industry would only spare them the token Asian spot and that spot had already been taken by Athena.

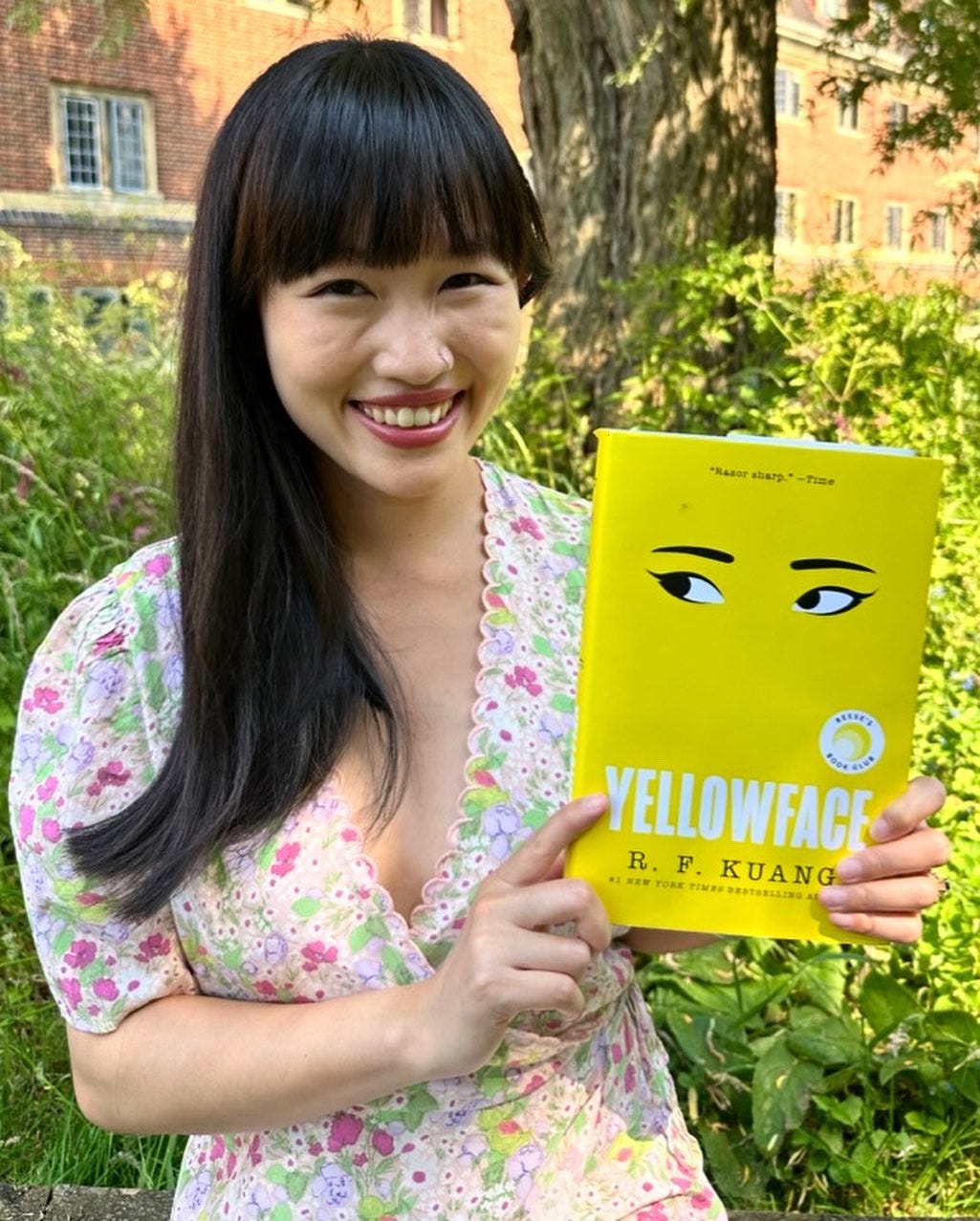

In an interview for Elle Magazine, Kuang elaborates on how her characters serve as insiders, showing the ugly truth about being an aspiring author and an immigrant in a competitive highly-monetized environment. She expounds on the burden of being tokenized through Athena’s story. That “cultural broker” role always imposes the question of whether an author deserves their success and limits their creative decisions to generational trauma and pain. Real stories of colleagues and fellow women of color in the industry “fueled into the rage that Candice Lee has” Kuang tells Elle. She’s weary of the competition-fueled rivalry in today’s literary environment and the silent notion that other people’s success comes at the expense of your own. Lastly, when asked about the book cover Kuang thinks Harper Collin’s artistic team did a clever job. The color yellow and the choice to display only an Asian pair of eyes on the cover abstracts the central theme of the book: the commodification of race can eclipse one’s personhood.

References:

Kuang, R. F. Yellowface. HarperCollins, 2023.

Buchwald, Ruth Minah. “R. F. Kuang on ‘Yellowface,’ Tokenization, and Asian Representation.” Elle, 22 May 2023, https://www.elle.com/culture/books/a43943728/r-f-kuang-yellowface-interview/.